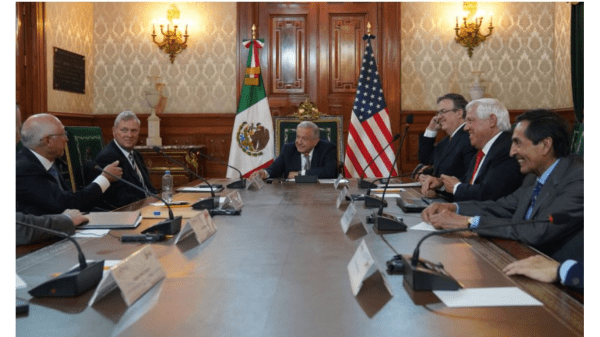

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack and Mexico Secretary of Agriculture and Rural Development Victor Villalobos met in early April on trade issues.

To the usually harmonious trade relations among the nations of North America, potatoes have proved an unhappy exception.

The U.S. ban on imports of the vegetable from Canada’s Prince Edward Island (PEI) has just been lifted, but exports of U.S. potatoes to Mexico remain limited to a 26-kilometer distance of the border between the two nations.

That appears to be changing.

On April 5, USDA secretary Tom Vilsack and Mexican secretary of agriculture and rural development Victor Villalobos announced an agreement stating, “The United States and Mexico have concluded all necessary plant health protocols and agreed to a final visit by Mexican officials in April that finalizes expanded access to the entire Mexican market no later than May 15 for all U.S. table stock and chipping potatoes according to the agreed workplan.”

The U.S. National Potato Council (NPC), which represents the $4.5 billion industry on legislative, trade, and other issues, expressed cautious approval of the agreement: “Given the history of this 25-year trade dispute, we are waiting to declare victory until we see durable exports of both fresh processing and table stock potatoes throughout all of Mexico as required by the November 2021 signed agreement. We hope the April site visit by Mexican officials will be the last hurdle we need to clear and that no last-minute roadblocks will be erected prior to Mexico finally—and permanently–reopening its border to U.S.-grown potatoes.”

Actually, the Mexican government had allowed the importation of U.S. potatoes in 2014, but this was challenged by CONPAPA (National Confederation of Potato Producers of the Mexican Republic, the Mexican equivalent of the National Potato Council). After years of legal wrangling, last April the Mexican supreme court ruled in favor of the U.S. industry.

But phytosanitary hurdles have remained. The latest agreement between Vilsack and Villalobos appear to have removed them, but the U.S. potato industry has reason for its reservations.

The NPC estimates that an open Mexican market could bring in $250 million per year within five years.

Trade disputes are particularly frustrating in that the ostensible reason for stoppage (say, phytosanitary concerns) is not the only, or often even the main, reason for them. Some PEI potato growers contend that the ban on their product was a move in a larger trade gambit, and U.S. potato growers can feel much the same way about Mexican restrictions.

The situation is especially complex because trade disputes are not one-dimensional—squabbling about potato imports is not just about potatoes, but is tied in with other, larger issues. The U.S.’s quickly reversed flash ban on Mexican avocados post-Super Bowl looks like part of the same picture.

Individual citizens often feel that they are often small fry caught in the intricate mechanisms of government. Entire industries can feel the same way.

To the usually harmonious trade relations among the nations of North America, potatoes have proved an unhappy exception.

The U.S. ban on imports of the vegetable from Canada’s Prince Edward Island (PEI) has just been lifted, but exports of U.S. potatoes to Mexico remain limited to a 26-kilometer distance of the border between the two nations.

That appears to be changing.

On April 5, USDA secretary Tom Vilsack and Mexican secretary of agriculture and rural development Victor Villalobos announced an agreement stating, “The United States and Mexico have concluded all necessary plant health protocols and agreed to a final visit by Mexican officials in April that finalizes expanded access to the entire Mexican market no later than May 15 for all U.S. table stock and chipping potatoes according to the agreed workplan.”

The U.S. National Potato Council (NPC), which represents the $4.5 billion industry on legislative, trade, and other issues, expressed cautious approval of the agreement: “Given the history of this 25-year trade dispute, we are waiting to declare victory until we see durable exports of both fresh processing and table stock potatoes throughout all of Mexico as required by the November 2021 signed agreement. We hope the April site visit by Mexican officials will be the last hurdle we need to clear and that no last-minute roadblocks will be erected prior to Mexico finally—and permanently–reopening its border to U.S.-grown potatoes.”

Actually, the Mexican government had allowed the importation of U.S. potatoes in 2014, but this was challenged by CONPAPA (National Confederation of Potato Producers of the Mexican Republic, the Mexican equivalent of the National Potato Council). After years of legal wrangling, last April the Mexican supreme court ruled in favor of the U.S. industry.

But phytosanitary hurdles have remained. The latest agreement between Vilsack and Villalobos appear to have removed them, but the U.S. potato industry has reason for its reservations.

The NPC estimates that an open Mexican market could bring in $250 million per year within five years.

Trade disputes are particularly frustrating in that the ostensible reason for stoppage (say, phytosanitary concerns) is not the only, or often even the main, reason for them. Some PEI potato growers contend that the ban on their product was a move in a larger trade gambit, and U.S. potato growers can feel much the same way about Mexican restrictions.

The situation is especially complex because trade disputes are not one-dimensional—squabbling about potato imports is not just about potatoes, but is tied in with other, larger issues. The U.S.’s quickly reversed flash ban on Mexican avocados post-Super Bowl looks like part of the same picture.

Individual citizens often feel that they are often small fry caught in the intricate mechanisms of government. Entire industries can feel the same way.

Richard Smoley, contributing editor for Blue Book Services, Inc., has more than 40 years of experience in magazine writing and editing, and is the former managing editor of California Farmer magazine. A graduate of Harvard and Oxford universities, he has published 12 books.