Years ago, I was teaching philosophy at a community college in western Massachusetts. Most of the students were blue-collar and were working part- or full-time.

One day the conversation turned to restaurant work. I was immediately offered a bouquet of horror stories. One student shared her reminiscences of preparing salad while standing ankle-deep in sewage.

Another memory: I was eating at a Cuban-Chinese diner on New York’s West Side that was not fastidiously maintained. I saw one of the cooks follow with his eyes something that was crawling along the floor. He cackled and stomped on it. “My God!” I thought. “A roach.” I looked over the counter. It was a mouse.

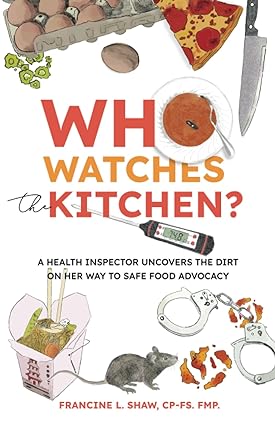

Such incidents are the topic of Francine L. Shaw’s new book, Who’s Watching the Kitchen?

Except not from the point of view of the hapless consumer but of a longtime health inspector and food safety expert.

Shaw chronicles her professional career from health inspector in a rural area where her predecessor did not take his job seriously to her present role as CEO of Safety Food and TracSavvy and a nationally recognized food safety expert.

Items:

“Did you know the number one restaurant in the world had a foodborne illness outbreak?” Shaw writes. Evidently true: Nora, in Copenhagen, in 2013.

In the United States alone, 48 million people a year (1 in 6 out of the population) contract foodborne illnesses, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die every year from food poisoning, says Shaw.

It’s all here: chain restaurant managers who keep cutting safety corners for the sake of company incentives, “so what was intended to be a motivational incentive program had become a massive risk to the company and to their customers’ health.” A walk-in freezer with freshly slaughtered baby goats. A restaurant that she closed immediately because of multiple severe violations, where one not very bright customer asked if he could finish his meal.

One chapter is “Celebrity Chefs Are a Thorn in My Side.” Not because they neglect food safety rules, but because their TV shows don’t show them modeling good practice.

Shaw writes: “I thoroughly understand that there are time constraints, and to spend twenty to thirty seconds washing their hands every time it was warranted would be boring. . . . But I believe they have a responsibility to, at a minimum, acknowledge that these programs are for entertainment purposes only and tell people not to cook that way at home.”

“What are you laughing at?” wrote the Roman satirist Horace. “Change the names, and the story’s about you.” Shaw’s account of the home kitchen is equally unsettling. It turns out that your dog’s dish is very likely more sanitary than your “coffee reservoirs, faucet handles, kitchen countertops, stove knobs, and cutting boards.”

Produce doesn’t feature much in this book, and then more as victim than culprit: in one establishment, Shaw writes, “I opened the walk-in cooler door, and as I entered, I saw four hog heads—yes, heads—sitting on the bottom shelf, immediately over produce on the floor. They had placed the hog heads directly on the shelf, so if anything dripped (and it did!), it landed on the lettuce, lemons, and limes underneath.”

You already know the ghastly truth: you, like me, have eaten in such establishments more often in our lives than we could possibly imagine. (At least we made it this far.)

Shaw’s book is lively, witty, well-written, and extremely informative about the never-ending health issues in the foodservice world.

Just don’t read it over lunch.