Apple Market Summary

Image: Africa Studio/Shutterstock.com

Apple Commodity Overview

Apple trees, Malus domestica, grow one of the most recognized and beloved fruits in America (as well as the rest of the world). During colonial times, the fruit was often called ‘melt-in-the-mouth’ or ‘winter banana’ for its texture and flavor.

Despite their popularity in America, apples can be found in European archaeological records dating back to before the Greeks; indeed, scientists recently traced the apple back even farther along the Silk Road to an early species in Kazakhstan, which cross-pollinated with the European crabapple.

Today, apples are an integral part of daily life and consumed fresh or processed in myriad forms—from drying, baking, and pickling to freezing and juicing. Apples can vary in color from yellows to greens to reds based on cultivar, of which there are more than 7,500 globally. Green and yellow varieties tend to be more tart in flavor, while red varieties are often sweeter.

Types & Varieties of Apples

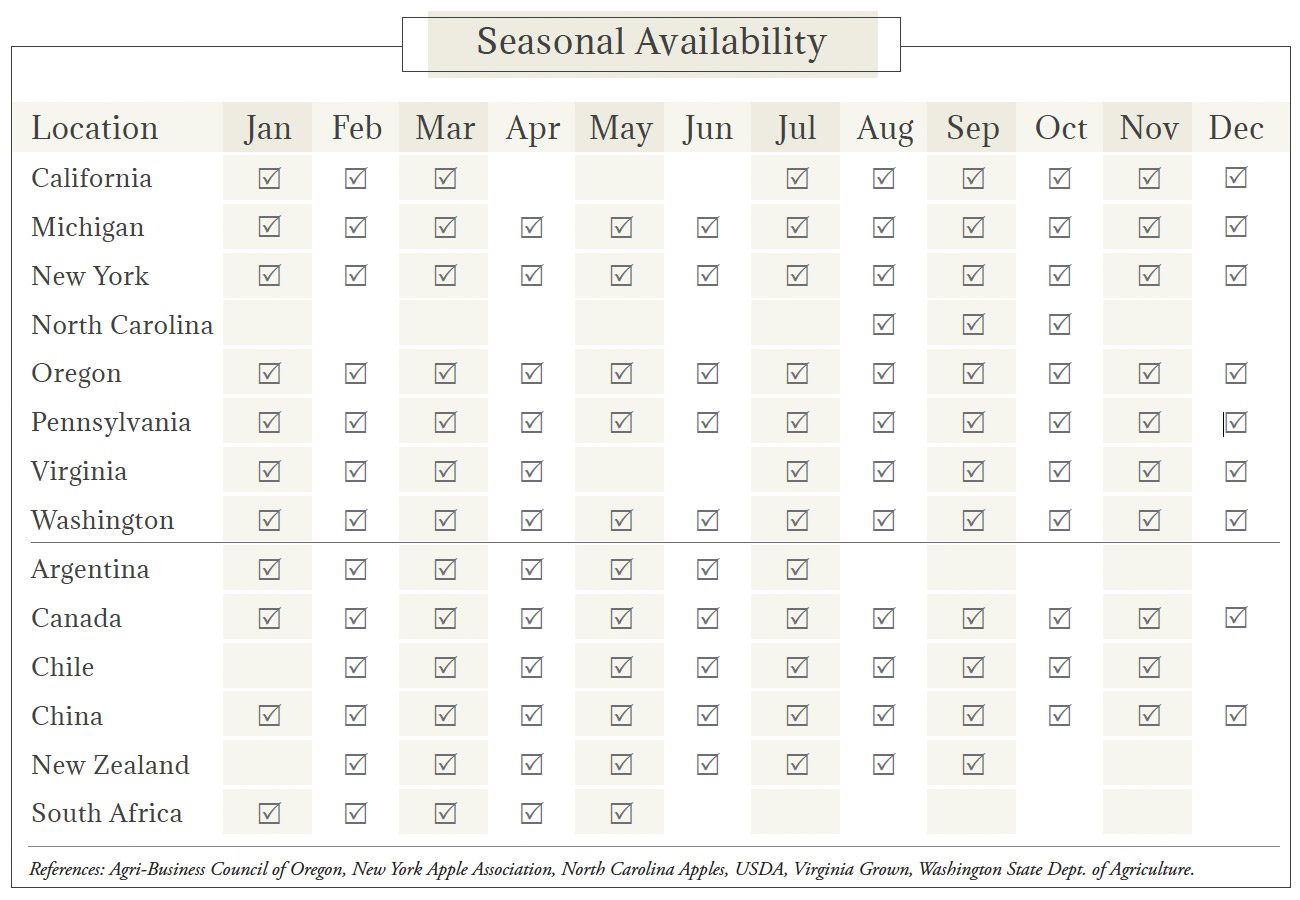

Although all types of apples are for fresh consumption, some varieties are better suited to pies and sauces or drying. Among the more familiar varieties are Ambrosia, Braeburn, Cameo, Cortland, Crispin, Empire, Fuji, Gala, Golden Delicious, Granny Smith, Honeycrisp, Jazz, Jonagold, McIntosh, Pink Lady, Red Delicious, Snap Dragon, SweeTango, and Zestar. About 100 varieties of apples are grown commercially in 36 states with Washington, New York, and Michigan dominating U.S. production.

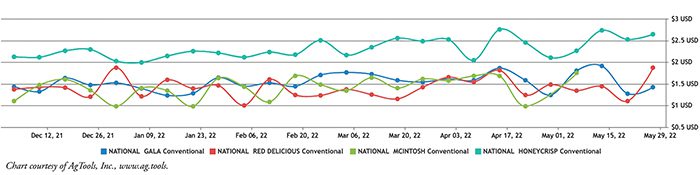

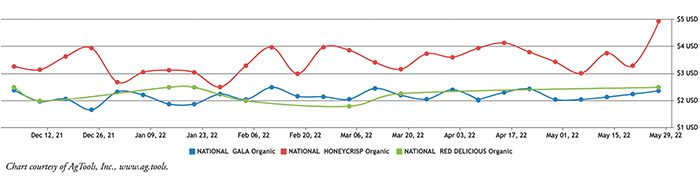

Apples range in flavor from sweet to very tart, and color depends on variety. Red Delicious are juicy, heart-shaped, ruby red apples with a mildly sweet flavor while Granny Smith apples are green, crisp, tart, juicy, and good for baking, sauces, juicing, eating raw, or for caramel apples. Galas are a pale red, round, and sweet, and are frequently dried or used in cider. Golden Delicious apples are yellow-green, crisp, and sweet; they are excellent for cooking as they maintain their shape well. Although organic varieties are gaining market share, conventionally grown apples still command the majority of retail sales.

The Cultivation of Apples

Well-drained soil with moderate to high levels of organic matter and ample sunshine are best for growing apple trees. Loamy soils with a pH level of 6.5 are optimal. Soil should be tested two years prior to planting to determine fertilizer and nutrient application levels.

It is important to control broadleaf weeds, as they lure bees away from the trees during bloom and can harbor harmful insects. Apple trees typically become productive, depending on type, with dwarf trees fruiting in 2 to 3 years and standard trees in 8 years.

Apples should separate easily from the spur and not be forced, as this may cause other fruit to fall. If spurs are taken with fruit, it may reduce the next year’s crop. After harvest, cool apples as soon as possible. Optimal storage temperature is 30 to 32°F with 95% relative humidity. Ripening apples give off ethylene, which can hasten fruit softening.

Pests & Diseases Affecting Apples

The apple maggot typically strikes in late June to mid-July; adults lay eggs in the summer inside fruit. Apple aphids appear in May through early July; the most prominent symptom is curling leaves. Shiny black eggs will be visible in early spring. Leafhoppers appear at the end of May or early June. They are white and feeding produces a stippled effect on leaves. The spotted lanternfly draws sap from plant stems and leaves after hatching in the spring or early summer. Adults grow to about an inch in length with large brightly colored wings. Other pests include the codling moth, plum curculio, mites, and scale.

Fire blight is a bacterial disease spread by insects, wind, and rain. Entire trees are at risk once infected. Apple scab is typical in humid, cool weather during the spring and common in the eastern United States, with the appearance of brown or green mold-like spots on leaves and fruit. Powdery mildew coats shoots and leaves, stunting growth and causing leaves to curl. Phytophthora crown and root rot are possible in wet conditions and often lead to browning and wilting. This water fungus is best prevented by ensuring good drainage in all parts of the orchard. Other diseases include bacterial spot, black rot, bitter rot, cedar apple rust, collar rot, and sooty blotch.

References: Clemson Cooperative Extension, Maine State Pomological Society, New York Apple Association, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, U.S. Apple Association, Washington Apple Commission, USDA.

Grades & Good Arrival of Apples

Apples can fall into a number of different U.S. grade categories, ranging from U.S. Extra Fancy, U.S. Fancy, U.S. No. 1, and U.S. Utility, to combination grades. The highest quality grade, Extra Fancy, will be of one variety, mature, clean, fairly well-formed, and free from decay, browning, internal breakdown, scald, scab, freezing injury, visible water core, or broken skin.

Generally speaking, the percentage of defects shown on a timely government inspection certificate should not exceed the percentage of allowable defects shown, provided: (1) transportation conditions were normal; (2) the USDA or CFIA inspection was timely; and (3) the entire lot was inspected.

| U.S. Grade Standards | Days Since Shipment | % of Defects Allowed | Optimum Transit Temp. (F) |

| 10-5-1 | 5 4 3 2 1 | 15-8-3 14-8-3 13-7-2 11-6-1 10-5-1 | 30-32° |

Canadian good arrival guidelines (unless otherwise noted) are broken down into five (5) parts as follows: maximum percentage of defects, maximum percentage of permanent defects, maximum percentage for any single permanent defect, maximum percentage for any single condition defect, and maximum for decay. Canadian destination guidelines are 15-10-5-10-4.

References: DRC, PACA, USDA.

Inspector's Insights for Apples

• There are minimum color requirements for a few varieties, such as Extra Fancy Red Delicious (66% of surface with good red color) and Extra Fancy McIntosh (50% of surface), but not for Gala, Braeburn, Fuji, Pink Lady, or other popular varieties

• Invisible water core is found internally and not visible without cutting the apple; it is not scored as a defect before February 1 of the production year or for U.S. No. 1, CAT 1, or Fuji apples

• Bruising is scored as a defect against Extra Fancy when exceeding an area of 5/8 or 1/8 inches in depth

• Surface mold, usually found affecting the stem cavity or calyx basin, is never scored as a defect; but mold found internally in the seed cavity is scored as a defect.

Source: Tom Yawman, International Produce Training, www.ipt.us.com.