Let’s see—where did the produce that is now in my house come from?

The Lucy Glo apples are from Chelan in Washington state. BB #:170403

I bought the avocados from Costco BB #:150902 in a mesh sack that I have long since thrown away, but the best guess is Mexico. The head of romaine in the refrigerator—Salinas, no doubt.

It’s starting to look old, and if my wife bought it, say, three weeks ago, it was probably before the Yuma crop was coming in. And the blueberries are from Peru (at least that’s what I remember from the clamshell before we threw that out).

In short, like most of the American produce supply, it is a medley from the Western Hemisphere.

This will come as no surprise at all to this audience. It will also come as no surprise that there is increased concern about the costs, environmental and otherwise, of this international panoply.

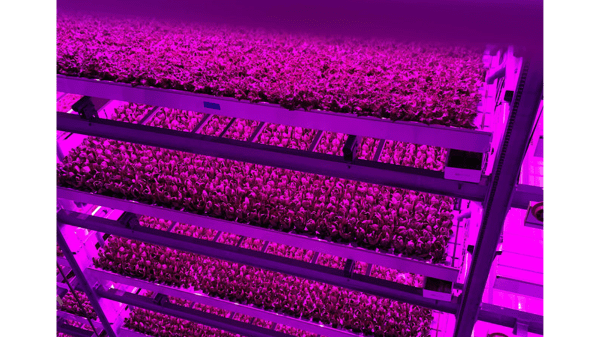

Fast Company has just come out with an article with the headline “40 Percent of the Produce in the U.S. Is Wasted. This Vertical Farming Startup Is Trying to Change All That”. It profiles 80 Acres in Cincinnati, a vertical farming company that sells only within a 50-100 mile radius of its facilities.

By the way, here’s the source cited for that 40 percent figure.

The destination for 80 Acres crops is going to supply some 300 Kroger BB #:100073 stores in the vicinity. As you may remember, Cincinnati is the headquarters for Kroger, meaning that if the company has a good experience with 80 Acres, it’s likely to look for similar opportunities in other metropolitan markets.

Eighty Acres was founded in 2015, with a single vertical farm that could supply about 80 acres’ worth of produce (hence, I guess, the name). Today it has eight operations, all in the Cincinnati area except for one outlier in Springdale, AR.

Cofounders Tisha Livingston and Mike Zelkind have shown a deft hand for both marketing and social responsibility: at the start of the pandemic, they operated a pop-up vertical tomato farm outside the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, dovetailed with an exhibit called “Countryside: The Future.”

“It’s Art,” proclaimed the Cincinnati Enquirer.

Whatever art theorists may make of this evaluation, the larger question for the produce industry here, as with vertical farms in general, has to do with cost.

“Food-supply chains today are very good, but they’re optimized for one variable, and that variable is cost,” says Zelkind. “We can get food almost anywhere, but you don’t get nutrition to a lot of these neighborhoods.” (“Vegetables can lose between 15% and 77% of their vitamin C within a week of harvest,” the Fast Company article contends.)

At this point, I have to wonder whether, apart from all else, the cost balance will start to favor such operations in the long run.

Let’s see: people in the industry have told me that today it can cost $15,000 to get a truck from California to the East Coast. Currently 80 Acres is delivering to nearby distribution centers, “growing our audience without growing our carbon footprint,” as Zelkind puts it.

Furthermore, every 80 Acres farm “uses 97% less water than traditional farming, since the crops grow without soil, rain, or sunlight,” says the article. The water issue is probably less urgent for fresh greens, because Salinas, the chief growing area, has had to keep groundwater levels high to prevent saltwater intrusion, meaning the region has been largely spared the water crisis afflicting the Central Valley. But that’s far from saying water isn’t an issue at all.

Labor? One big difference: a vertical farm can guarantee year-round employment in a way that open-field growers cannot. So even if you set aside the cost of hourly wages, there is a real cost to an increasingly erratic supply of seasonal labor common in open-field agriculture.

The H-2A program is expensive, and even if a grower has been able to rely on the same workers showing up in season each year, current disruptions (the pandemic, the continuing border crisis) make that less and less certain. There’s a cost in the simple act of trying to find workers: you have to put man-hours into the search that could be spent on more profitable enterprises.

So far, the advantages of vertical farming have been seen as its perceived environmental sustainability and the chic of eating locally grown foods. But I have to wonder at what point the cost balance will shift in the opposite direction.