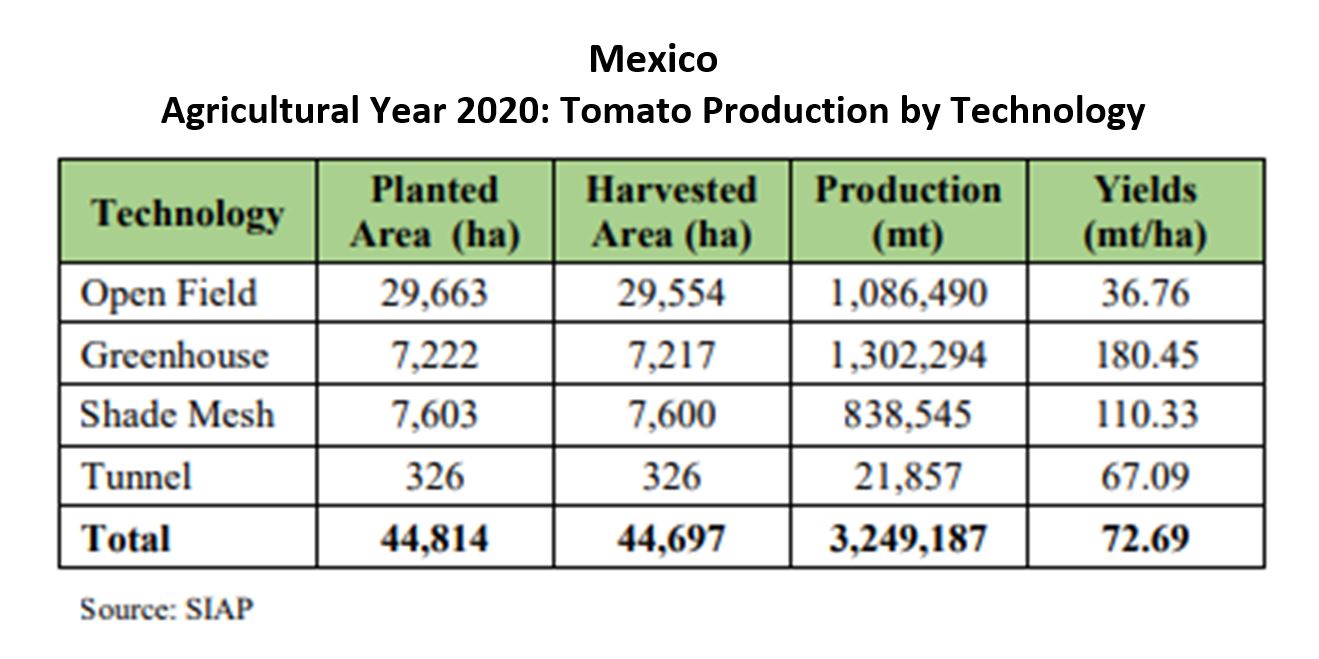

According to the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service’s 2021 Tomato Annual Report, Mexico’s SIAP (Agrifood and Fisheries Information System) cites an estimated 80 percent of Mexican tomato exports coming into the United States are grown under protection.

This is a key factor in the increasing volume from the country, which rose 20.6 percent last year, with a record-breaking value of $2.6 billion.

Mexico is the largest exporter of tomatoes worldwide. Sinaloa in northwestern Mexico is the country’s top tomato-producing state for fall and winter production, supplying the U.S. market from December through May.

This coincides with Florida’s growing season and is the cause of ongoing tension between the two producers. During the summer months, supplies come from Mexico’s central region, while from May to December tomatoes are exported from Baja California and Baja California Sur on the country’s western coast.

The Mexican government provides substantial support for protected agriculture, with incentives covering up to 50 percent of the investment cost.

In 2017 Mexico’s Secretary of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries, and Food (SAGARPA) projected a substantial tomato production increase of 46 percent and export capacity surge of 77 percent from 2016 to 2024. The country is certainly making strides on this predicted growth.

Rules, controversy, viewpoints

About 80 percent of Mexican tomato imports to the United States are Romas, which have gained in popularity among consumers of all ages.

Last year, the USDA proposed bringing previously exempt Roma tomatoes under the federal marketing order for tomatoes grown in Florida, as recommended by the Florida Tomato Committee.

The latter also recommends developing exemption language for greenhouse and hydroponic tomatoes by establishing a new definition for “controlled environment” and changing pack and container requirements to reflect current industry practices. But in April of this year, the USDA withdrew its proposal after receiving feedback from industry stakeholders.

Unfair trade practices by Mexico have been a hot button issue for the Florida produce industry for years. The Tomato Suspension Agreement, revamped and signed in 2019, sets a price floor and requires inspections of tomatoes for quality and condition upon entry to the United States from Mexico.

Designed to prevent Mexican imports from undercutting domestic fresh tomato price levels, it continues to raise hackles within the United States and in Mexico. Many question its effectiveness.

“It is effective, but not as much as it was intended to be,” says Elmer Mott, vice president of Collier Tomato & Vegetable Distributors, Inc., BB #:126248 a brokerage firm in Arcadia, FL, who insists there are ways to get around the agreement.

More changes?

This past summer the Fresh Produce Association of the Americas accused the Florida Tomato Exchange of pressuring the U.S. Department of Commerce to change the definition of free-on-board or FOB as related to the Agreement, which, the organization claims, would increase prices.

“The Florida Tomato Exchange is not seeking a renegotiation or change to the 2019 agreement,” answered Michael Schadler, Florida Tomato Exchange executive vice president, in a press release.

“We simply want the language and rules to be enforced as they were written and agreed to in 2019 by the Commerce Department and the Mexican tomato industry. Otherwise, this agreement will fail like all the others before it.”

The reference price includes expenses incurred in Mexico as well as all expenses incurred on the U.S. side of the border.

Jimmy Connell, president of Keith Connell, Inc., BB #:105626 of Kansas City, MO, is a tomato broker. About 80 percent of his year-round supply of tomatoes comes from Mexico.

Connell has a warehouse in Nogales and leases one in McAllen. “We’ve been thinking about purchasing our own warehouse in McAllen instead of leasing. We’re just trying to find the right location.”

The company distributes nationally, with a concentration in the Midwest and Upper Midwest, and predominantly within the foodservice industry.

Connell believes the Tomato Suspension Agreement only benefits a few. “It hurts the American end user in the long run,” he explains, “because you have to pay higher prices for Mexican tomatoes.

“Mexican shippers are frustrated with all the paperwork involved,” Connell adds, “and some have cut back on their crop. Less crop will increase pricing.” Although this has yet to happen, he says, “We’ll see.”

This is an excerpt from the Tomato Spotlight in the November/December 2021 issue of Produce Blueprints Magazine. Click here to read the whole issue.