Founded in 2000, Mac’s Creek Winery & Brewery in Nebraska suffered a devastating loss in 2013 when nearly all of its 4,000 grapevines were destroyed by herbicidal drift.

Fighting back from disaster spurred the family-owned business to turn to drones as a tool for preventing another such loss.

Given the location of its vineyard, near fields of row crops, Mac’s Creek was at risk of more drift incidents.

So the winery’s management decided look into how drones could be used to monitor vines. With a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the company equipped drones with cameras to look for signs of any damaging effects of herbicidal drift in a handful of its 25 acres.

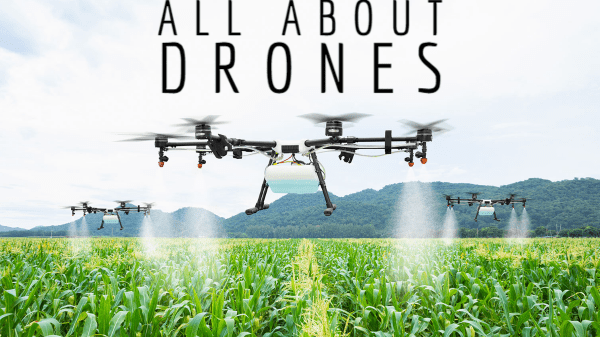

Mac’s Creek is far from alone in this effort. Both researchers and growers throughout the country are delving into drones to see how effectively they can monitor crops, detect emerging problems, and treat plants against pests or diseases, as well as save time, money, and labor.

An Eye in the Sky

Using drones, or unmanned aerial vehicles, in agricultural applications remains a relatively new phenomenon. While drones have been widely used in the government and military sectors for more than two decades, authorization for general use in agriculture didn’t come until 2015.

Nonetheless, the size of the agricultural drone market is expected to soar. It was $300 million in 2016, according to the research and management consulting company Global Market Insights, which predicts it will grow to $1 billion by 2024.

Drones are better known for use in growing grains like wheat, corn, and soy. This perception is evolving, however, as researchers launch drones equipped with cameras, beneficial insects, crop sensors, or other technologies to see how they can help growers of fruits and vegetables produce healthy and abundant yields.

“We’re very interested in precision agriculture,” says Christian Nansen, associate professor in the Department of Entomology and Nematology at the University of California, Davis. “We want to be as precise as we can in applications, and we need to find when and where we have emerging problems.”

One aspect of Nansen’s research involves trying to detect when strawberries or almonds are distressed, which can be seen by how they reflect sunlight.

“We’re using very sensitive cameras to take the temperature of a crop and identify what’s causing stress,” he says. “We’re learning more and more about how imaging data from growing plants can be used not only to determine whether they’re stressed or not, but also to diagnose the stressor.”

Different stressors can affect plants in many ways.

“It’s just like how our immune system responds differently to the common flu compared to other diseases or stressors.”

For Max McFarland, one of the owners at Mac’s Creek, it wasn’t necessary to equip the drones with highly specialized cameras to try to detect herbicide drift. Images depended on the thickness of the canopy, but McFarland says they were just as good as if he had walked the vineyard himself.

Even if an image triggered a false-positive result, he says the effort wasn’t wasted.

“It’s much better to think there’s damage and to look for it, than to not look and not realize it was there. The sooner you find it, the sooner you can detect where it came from and intervene.”

This is an excerpt from the Applied Technology feature from the May/June 2021 issue of Produce Blueprints Magazine. Click here to read the whole issue.